In a shocking revelation, victims of enforced disappearances in Bangladesh have come forward to share their harrowing experiences in secret prisons allegedly run by the country’s military intelligence. The testimonies of Michael Chakma, a Bangladeshi Indigenous rights activist, and Mir Ahmad Bin Quasem, a lawyer, expose the brutal conditions and dehumanizing treatment of detainees in these clandestine facilities.

Chakma, who was held for five years, described his detention as “harrowing and filled with unending despair.” He was kept in a windowless room, handcuffed and shackled, with no way to tell time or whether it was day or night. “I was in a dark, enclosed space, and when the light was turned on, it was too bright for me to see properly,” Chakma told Al Jazeera. “Most of the time, I was handcuffed and shackled.”

Quasem, who was missing for eight years, shared similar experiences, including being held in a windowless room with a constant hum of an exhaust fan, making it impossible to hear outside sounds. “Our health was regularly monitored. We received decent food, but just enough to keep us alive – nothing more, nothing less,” Quasem said.

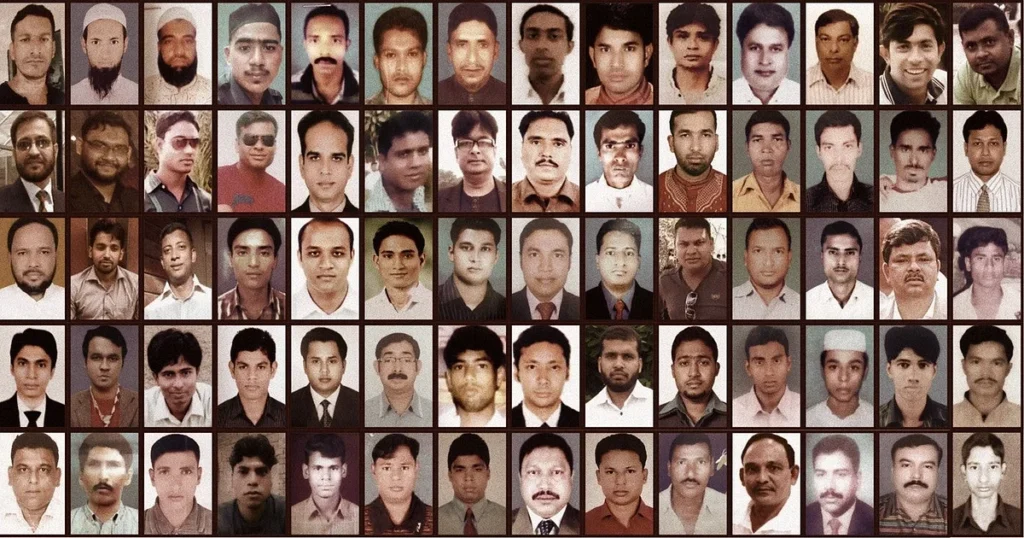

Their stories are not isolated incidents. Over 700 people, including top opposition figures and activists, were forcibly disappeared during the 15-year rule of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Of these, 83 victims were later found dead, and more than 150 individuals remain missing.

The interim government, led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, has formed a commission to probe the disappearances and recently signed the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances. However, families of the victims continue to wait for information about their loved ones, and many are still missing.

The testimonies of Chakma and Quasem highlight the need for accountability and justice for the victims of enforced disappearances in Bangladesh. As the country moves forward, it is essential to address these grave injustices and ensure that such human rights violations never happen again.

Chakma’s ordeal began in April 2019 when he was picked up by armed men near Dhaka for his criticism of the Hasina government’s policy on the Chakmas, the largest among Bangladesh’s Indigenous groups. He was allegedly held in Aynaghar (“House of Mirrors”), a notorious network of secret prisons operated by the military intelligence.

Quasem, a lawyer, was abducted in 2016 and kept in a similar facility. He described the conditions as “dehumanizing” and said that detainees were regularly monitored by doctors to ensure they stayed alive.

The families of the victims have suffered greatly, living in uncertainty and waiting for any information about their loved ones. Nadira Sultana, Quasem’s wife, said that her daughters still believe their father is alive. “I told them I would bring him back,” she said.

Sanjida Islam Tulee, coordinator of Mayer Daak, a rights group dedicated to combating enforced disappearances in Bangladesh, praised the government’s decision to address the issue. “The grave injustices of these disappearances must be uncovered and prosecuted,” Tulee said. “Many families are still waiting for their loved ones to return. They deserve the answers.”

As Bangladesh moves forward, it is crucial to ensure that those responsible for these human rights violations are held accountable and that measures are taken to prevent such abuses from happening again. The victims of enforced disappearances and their families deserve justice and closure.